Writer and poet nayyirah waheed has a piece which reads,

"if i write what you feel but cannot say. it does not make me a poet. it makes me a bridge. and i am humbled and i am grateful to assist your heart in speaking.” - grateful

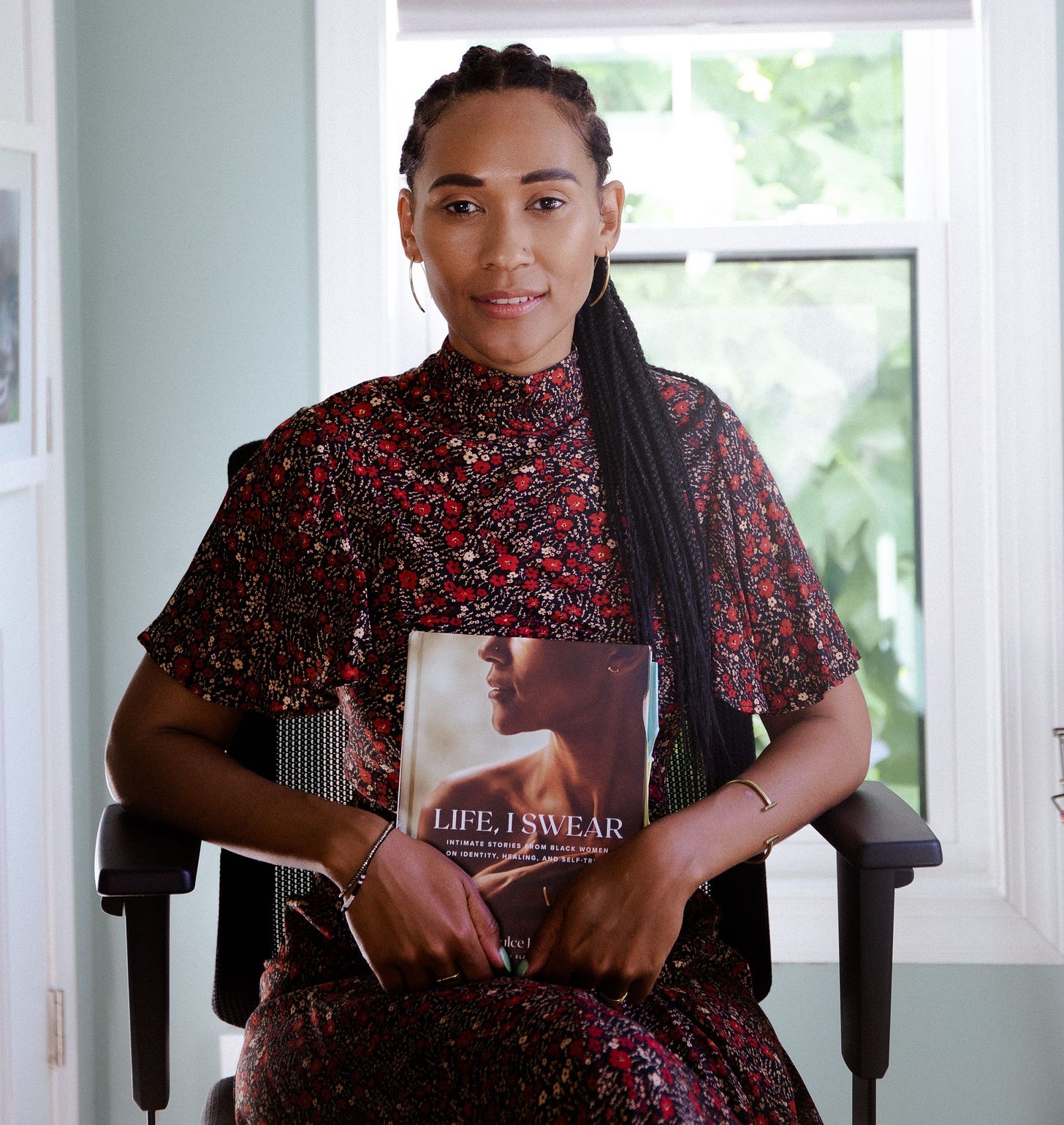

In the summer of 2020 I met a woman who I found not only to be a kin of my heart but one who has assisted in its speaking. This Sunday's letter is deeply personal. A conversation between myself and author, mother, daughter, storyteller, lover, sister and friend, Chloe Dulce Louvouezo.

We hope you enjoy.

Chloe Dulce Louvouezo is a woman whose spirit, energy and presence is beyond description. But, for the sake of those for whom this will be their introduction, I will paint you a picture. I don’t know in what past life, or spiritual plane, Chloe and I previously met but I knew her before ever knowing her. Her heart knows mine. They speak the same language.

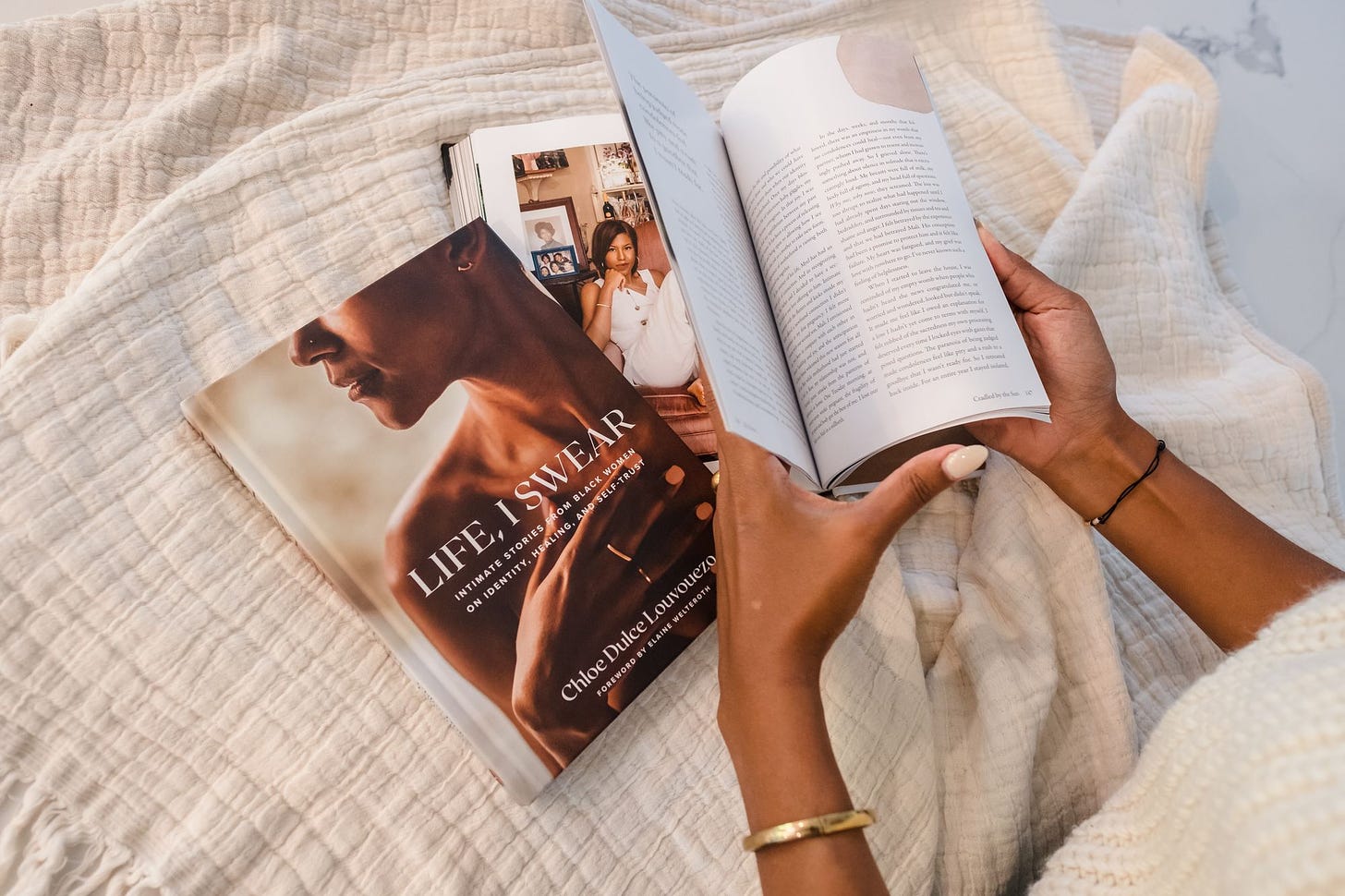

Congolese-American, writer, mother, daughter, sister-friend and now author, Chloe has a way with language, written and spoken. Her debut book, Life, I Swear: Intimate Stories from Black Women on Identity, Healing, and Self-Trust is a memoir chronicle of transformation and growth by and for modern-day Black women. The book features the journey stories of some of today’s most influential Black female voices and I am honored to be amongst them. The book, which carries the same title as her exquisitely produced podcast, is a necessary disruption to the soul, one that, line by line, will touch and feel into your inner most tender spaces. It is a work of heart, one that pulls at your strings, orchestrating a moving melody.

The following conversation is informed by four parts: Seed, Soil, Harvest and Sowing. The title, as well as these parts, are inspired by the meaning of Chloe's first and middle name: Chloe, meaning growth, and Dulce meaning sweet. And, indeed Chloe Dulce Louvouezo is growing sweetly.

Seed.

“I see words and story as a form of art which involves discovery.” - Chloe Dulce Louvouezo

ENIAFE ISIS: I am a believer in moments of impact. The moments in our lives when a particular desire or fascination is first planted within us. These fascinations may serve as guides throughout our lives, calling us to pursue specific purposes and passions, and the desires are often what inform our channels of expression and perspective. What was the moment of impact for Life, I Swear?

CHLOE DULCE: I’ve always been fascinated with the mystery of other people’s lives. The idea that there is dignity in every person’s story was one of my earliest life lessons. Moving around a lot growing up, I always acclimated quickly to new environments and would tap into how friends and their families interpreted the world differently and what their motivations and reasoning were, specific to their experiences. I later incorporated this fascination into my work at a large human services agency in New York City called Services for the Underserved which primarily serves people experiencing mental illness. During my visits with individuals, I’d step into their homes and listen to them narrate events in their lives when they felt most vulnerable. I think this was a moment of impact, when the idea of healing through storytelling became a passion and it’s been a passion of mine ever since.

EI: The individuals you worked with, would they tell you about these events on their own or was it your invitation for them to share that prompted their telling?

CD: Both. It was my job to be a storyteller. They volunteered to share and were often excited to do so. For many, it was the first time they felt they were being heard and their story was being valued. There is so much we can assume about others based on what we think we know about them. When we are unaware of the key aspects of someone’s story, the parts that inform the sum of who they are, we miss windows of opportunity for deeper understanding.

EI: I love your phrasing of this. Windows, like lenses or looking glass. Would you say that the window is just as much of a lens that allows others to see us, as it is for us to see and also seek ourselves?

CD: Absolutely yes. I see words and story as a form of art which involves discovery. I became a mother at 30 and as I stepped into motherhood, I needed to discover parts of myself, that I hadn’t yet tapped into, and unearth others I had lost, and integrate the two. In the original conception for Life, I Swear, I ruminated on writing something that would one day be printed but was content with it being a single copy that I would hold in my hands and archive for my children to better understand me. I wanted an artifact to be left behind as evidence of the woman I was before I had become a mother. I hadn’t yet imagined that this would be an artifact that would live beyond my family files.

EI: You have so many stories of your own which you share and I imagine there are still more to share. What led your decision in choosing to curate a collection of essays with other Black women and not just write a memoir?

CD: When I finally decided that my stories would be ones I shared with more than just my family, I was adamant about including them in a collection of narratives from other multilayered women. I wanted to offer a body of work that would broaden readers’ perspectives and enlighten our thinking around identity and healing. I believe that every point of view can lead us to a different realm of truth. Meaning that while Black women may all experience life with a common denominator--one that unifies us and cultivates empathy in our understanding and love for each other--the nuanced details of our individual lives creates different realities and paints a larger and more nuanced picture. Gathered and presented together, our stories become a sort of mosaic revealing how beautifully textured Black women are as a collective. Our stories allow us space to reimagine and redefine what it is to be Black and woman.

EI: Why is this space, for our reimaging and redefining, so important?

CD: I think it’s important for us to remember how limiting the idea of a linear path is. It emphasizes perfectionism along a very straight and rigid progression through life. It’s not realistic and it’s dehumanizing, particularly for those of us who either desire to live more creatively and out of the box, or who don’t benefit from the expectation to live life in a certain way. When we are able to witness how women are choosing to live, heal and celebrate themselves on their own terms, and are more full spiritually because of it, it gives other women permission to be curious and liberty to do the same.

Soil.

" I’ve always considered myself to be a resilient person, agile and able to pivot positively event after deeply distressing experiences. But there is a difference between being resilient and being immune to pain." - Chloe Dulce Louvouezo

EI: What has the journey been like realizing that you are, in fact, the soil within which this work could be actualized? And have there been, and are there still moments of doubt and paralysis?

CD: It took me going through the entire process of writing, collecting, editing, pitching, designing, publishing and receiving the final digital galley copy--and hearing you screaming on the other end of the line while looking at the same galley--to finally accept the idea that I am the unique vehicle for this body of work. I knew the collection as a whole was and would be powerful when collated together and that my own stories are quite layered, but it took other people like you affirming this work before I understood my assignment to make it come to life. Until then, doubt hovered over the journey from book editing to its release.

While I celebrated the contributors in the book, I still struggled to celebrate myself. The anticipation and discomfort of thrusting myself into new spaces was, for a moment, paralyzing. The paralysis pushed me to better understand my own hesitation in accepting myself as the soil. Writing this book healed many wounds, it also exposed others. The silver lining is that I now understand that exposure, as well as rawness, are necessary for continued healing.

EI: What wounds were exposed and/or made more raw?

CD: This process revealed a deeper feeling of insecurity than I realized I had. I’ve always considered myself to be a resilient person, agile and able to pivot positively event after deeply distressing experiences. But there is a difference between being resilient and being immune to pain. In many cases, I had moved on too quickly, dismissing just how much the residue of toxic experiences or dysfunctional relationships still lingered. In the making of this book, those wounds surfaced as a plague of self-doubt. But as one of my new favorite poets, Teri Ellen Cross Davis, recently said to me: “Our inferiority is worth exploring.” As a responsibility to my healing, I needed to follow through in mending those wounds. I’m still working on this.

EI: There's this line I've written, originally in response to an interview question, "What have been the hardest pieces to write?" My response is that the hardest pieces are the ones I haven't written yet, the one's where the words don't flow or the flow is one that scares me. Was there any part of Life, I Swear that was particularly challenging to write out/write through?

CD: If I could say all of them, I would. But my two essays on identity were hardest to write through. In these essays I share my experience of growing up biracial, bi-continental, multi-cultural and living a very transient life from a young age; moving between cities, countries, and the homes of several friends and their families. It was a very dynamic life that was rich with experiences and insights and I’m forever grateful for how unique of an upbringing I had. It’s central to who I will always be and how I see the world. It was also a lonely experience to toggle between all of these communities as a girl without long-standing roots in any of them because I relocated frequently and my family was so spread out and unfamiliar to me. The biggest challenge in sharing this part of my story was articulating the complexities of my experience: balancing two worlds in Niger, where I grew up, my Congolese and American families, navigating the social norms of the culture of Islam, being an American living in Africa, being an African living in America, and living among other families from around the world. These experiences taught me a lot about the idea of belonging and what home means to me and while its intricacies were hard to describe, it was in the unpacking that I was able to reaffirm my identity and articulate it in a way I wasn’t able to as a girl.

Harvest.

“I consider [Life, I Swear] a crop that is poised to be harvested and ready to be fed to others, eaten and digested slowly.” - Chloe Dulce Louvouezo

EI: The definition of harvest is: the process of gathering a ripe crop from the fields. I want to focus on this word "ripe". Would you say Life, I Swear is a product or outcome of your harvest, your ripening, or would you say that your ripening is a result of the book?

CD: I love this question, and I’d say the latter. The decision to curate this book marked my readiness for a deliberate healing journey, and I consider the completed book evidence of having gone through that journey. This creative project really required all of me. In committing to the book, I surrendered to the ways it would entail me to be pulled, stretched and questioned. From journaling from a place of pain, to revisiting my own perspectives through the editing process, to the audacity it took to convince the contributors and even myself of the bigger vision for Life, I Swear. This project was a very emotional and spiritual process for me. I would equate it to weeding, pruning, trimming, and shaping of soil.

The personal breakthroughs that happened along the way were like petals finally turning outward toward the sun. It’s all very metaphorical but through this process, I saw myself expand and ripen. And now I consider this book to be a crop that is poised to be harvested and ready to be fed to others, eaten and digested slowly. It’s my biggest joy to have created something that reflects my own growth and hopefully also supports that of other Black women.

Sowing.

“Liberation is the questioning and dismantling of the frameworks that don’t fit who we are, it’s rebellion. Liberation is loving ourselves beyond and outside of worldly limits.” - Chloe Dulce Louvouezo

EI: I love a double entendre so looking at this idea of sowing as such, what do you hope to sow and sew with Life, I Swear? What will be planted, what can be healed and what do you want this book and the stories that live in it to mean to the collective of Black women as well as non-black readers?

CD: Storytelling isn’t new among Black women; the words of many writers and poets have helped us heal and feel seen and serve as anchors, as references when we don’t have the words to articulate our own feelings. As an evolution to our collective storytelling, it’s powerful to see how a group of diverse writers that represent today’s Black women express their feminism, their advocacy around self-love, their maturity around grief and forgiveness, and their pursuit for understanding themselves, their ancestors and their communities. Myself and the other contributors in this book have recounted experiences of pain and joy, many with detailed transparency that is often lost when we zoom too far out and lump Black women into a singular identity or experience. My hope is that the words in this book confirm how nuanced we are and help mend and heal any narratives about Black women’s value being one dimensional.

EI: You have said that much of this book is about breaking away from confines, conforms, and limitations so that we can live at our highest vibration/potential. As we think about the idea of being able to be our freest selves, what does liberation mean to you?

CD: In its simplest sense, I believe liberation is loving ourselves without caveats. There are enough societal messages that have shaped our measures for success from very early stages in our lives and through our careers, to the point of only loving ourselves conditionally. I think there are a lot of ideals we adopt that frame our unhealthy desires or produce spiritual imbalances that are tucked away in our subconscious. So while self-love may be something we highly regard or aspire to, it’s nearly impossible to translate into practice, in how we treat or speak to ourselves, when the other side of our brain is still seeking validation from a framework that minimizes us. To me, liberation is the questioning and dismantling of the frameworks that don’t fit who we are, it’s rebellion. Liberation is loving ourselves beyond and outside of worldly limits.

"I believe we’re all qualified to tell our stories and some of the most powerful stories are from those who have been the most stigmatized, overlooked, and underserved. I work to capture a true narrative of communities and individuals, their pain points, and their resilience through their humanness. Storytelling can be a powerful tool for personal and collective healing and understanding, and by surfacing these nuances we can inspire and inform humanity." - Chloe Dulce Louvouezo